Advantages

This production pathway benefits from established technologies and extensive industrial-scale implementation globally.

The processes involved, primarily fermentation and distillation, are relatively simpler and well-understood.

Professional with many years of experience as a Site Manager, Project Manager, and Senior Expert in a leading multinational company in the chemical-food sector. Results-oriented approach, with a strong focus on managing highly specialized teams and complex projects at local and European levels.

Tech News.

Introduction

Bioethanol, a renewable biofuel derived from biomass, plays a pivotal role in diversifying energy sources and mitigating greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. This report provides a comprehensive examination of bioethanol production, distinguishing between first-generation (1G) and second-generation (2G) approaches. It details the intricate processes involved in extracting carbon dioxide (CO2) from these facilities and critically analyzes the multifaceted challenges associated with CO2 quality. While 1G bioethanol, primarily from food crops, offers established production pathways, it faces significant sustainability concerns due to competition with food supplies and indirect land use change (iLUC) emissions. Conversely, 2G bioethanol, utilizing non-food lignocellulosic biomass and waste, presents a more sustainable alternative but is currently hampered by high production costs and lower technological maturity.

A key aspect of bioethanol's environmental benefit lies in its potential for carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS), particularly through Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage (BECCS). Bioethanol plants are uniquely positioned as ideal candidates for CO2 capture due to the high purity of the CO2 stream generated during fermentation. However, achieving net negative emissions necessitates capturing additional CO2 from byproduct conversion processes. The quality of captured CO2 is paramount, as impurities can severely impact its suitability for various industrial and commercial applications, ranging from beverage carbonation to enhanced oil recovery and chemical synthesis. Strict purity standards are essential to prevent equipment damage, ensure product integrity, and maintain safety, highlighting the complex interplay between process technology, environmental goals, and economic viability in the evolving bioethanol industry.

Introduction to Bioethanol Plants

Bioethanol, frequently referred to simply as ethanol, stands as a crucial biofuel derived from diverse biomass materials rich in sugars, starches, or cellulose. Its fundamental objective is to serve as a sustainable alternative to conventional petroleum-based energy sources, particularly within the transportation sector. This renewable energy source offers substantial environmental and economic advantages, including a notable potential for reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Depending on the specific feedstock employed, bioethanol can achieve GHG savings of up to 80% when compared to fossil fuels.

Beyond its primary function as a fuel, bioethanol is widely utilized as an additive to gasoline. Blending bioethanol with gasoline has several benefits, such as reducing carbon monoxide and other toxic pollutants emitted from vehicle exhausts, and enhancing octane levels in the fuel mixture. The production of bioethanol is inherently linked to the natural carbon cycle. Plants, through photosynthesis, capture carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere and convert it into energy-rich carbohydrates. This process allows plants to function as a "natural battery," storing the sun's energy, which is then released when the biomass is harvested and converted into bioenergy. This cyclical nature of carbon is foundational to the concept of sustainable bioenergy.

Bioethanol, frequently referred to simply as ethanol, stands as a crucial biofuel derived from diverse biomass materials rich in sugars, starches, or cellulose. Its fundamental objective is to serve as a sustainable alternative to conventional petroleum-based energy sources, particularly within the transportation sector. This renewable energy source offers substantial environmental and economic advantages, including a notable potential for reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Depending on the specific feedstock employed, bioethanol can achieve GHG savings of up to 80% when compared to fossil fuels.

Beyond its primary function as a fuel, bioethanol is widely utilized as an additive to gasoline. Blending bioethanol with gasoline has several benefits, such as reducing carbon monoxide and other toxic pollutants emitted from vehicle exhausts, and enhancing octane levels in the fuel mixture. The production of bioethanol is inherently linked to the natural carbon cycle. Plants, through photosynthesis, capture carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere and convert it into energy-rich carbohydrates. This process allows plants to function as a "natural battery," storing the sun's energy, which is then released when the biomass is harvested and converted into bioenergy. This cyclical nature of carbon is foundational to the concept of sustainable bioenergy.

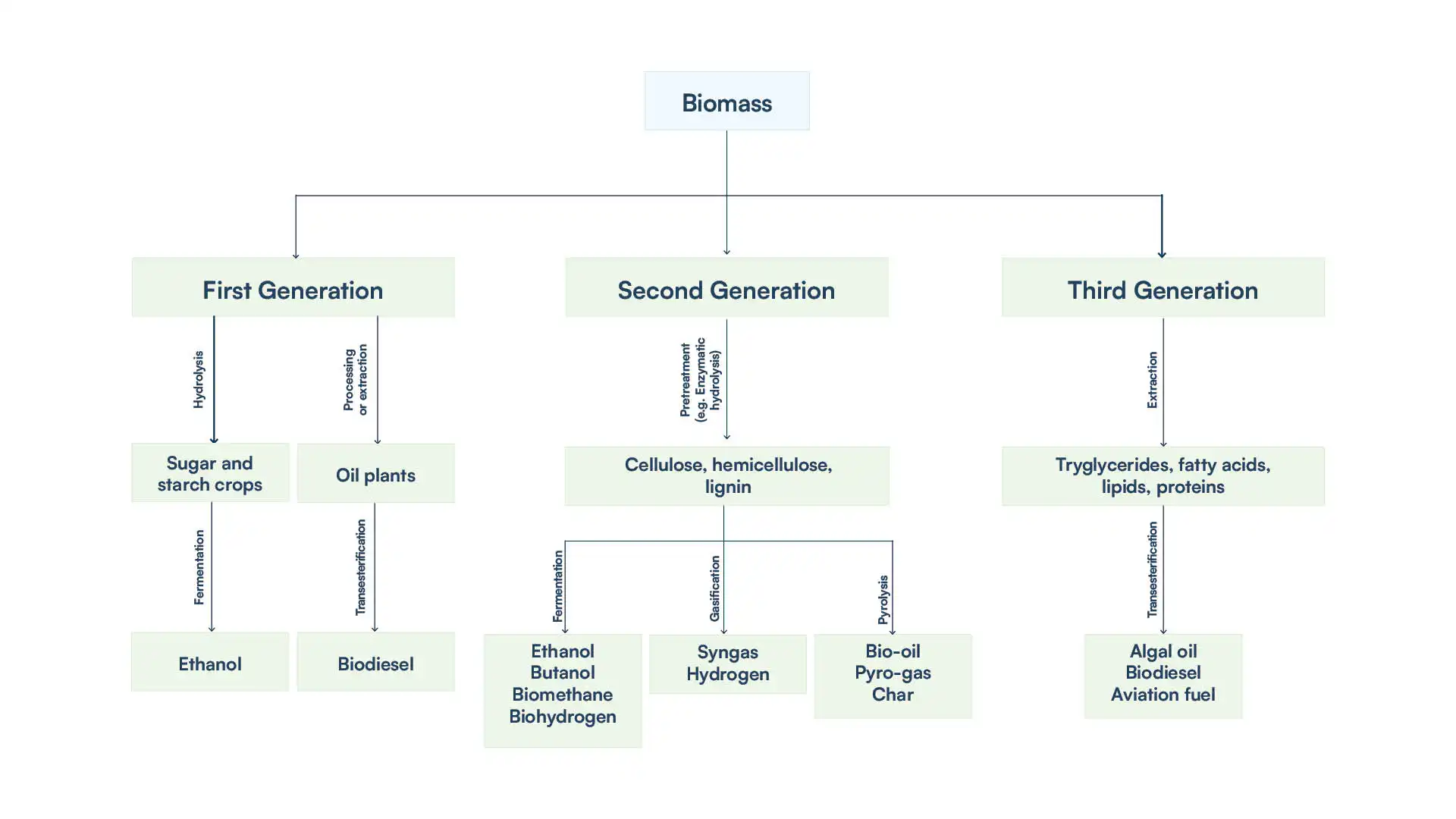

Overview of Bioenergy Feedstocks and Production

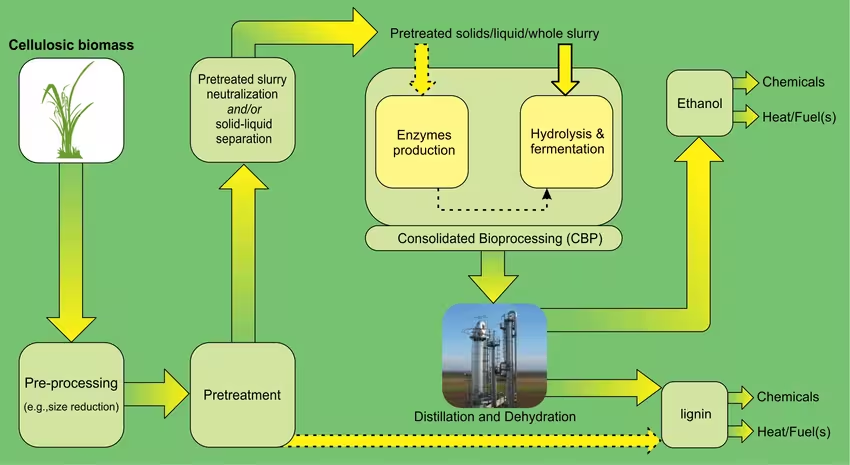

Second generation Bioethanol Plant

First-Generation Bioethanol: Production and Feedstocks.

Characteristics and Typical Feedstocks.

First-generation (1G) bioethanol production is characterized by its reliance on sucrose and starch-rich feedstocks, which are predominantly edible agricultural crops. In the United States, corn serves as the primary feedstock, accounting for over 90% of ethanol production. Brazil, the world's largest producer of ethanol, predominantly uses sugarcane. Other common 1G feedstocks include sugar beet, wheat, barley, milo, potatoes, and cassava. These feedstocks are widely available, and the technologies for their conversion into ethanol are well-established and have reached industrial scale.

Production processes

The fundamental process for 1G bioethanol involves the anaerobic fermentation of sugars into ethanol and carbon dioxide, primarily facilitated by yeast.

For sucrose-containing feedstocks, such as sugarcane or sugar beet, the juice or molasses (a byproduct of sugar processing) is often directly fermented. Prior to fermentation, the sugar concentration is typically diluted to an optimal range of 14-18% to support efficient microbial growth. Research efforts in this area often focus on identifying and optimizing yeast species and fermentation conditions to maximize ethanol yield while minimizing the formation of undesirable byproducts like glycerol and foam.

For starch-containing feedstocks, such as corn or wheat, the conversion process is more involved and typically comprises several key operations:

- Milling: The grains are initially milled to break them down into smaller particles. This can be achieved through either wet milling, which fractionates the grain into starch, fiber, and germ, or dry milling, which processes the whole grain. Dry milling is a common method for corn-based ethanol production.

- Liquefaction: The milled starch is mixed with heated water to form a mash or slurry. Enzymes, such as α-amylase, are then added to break down the complex starch molecules into smaller dextrins.

- Saccharification: A second type of enzyme, glucoamylase, is introduced to further hydrolyze these dextrins into simple glucose monomers, which are readily fermentable sugars.

- Fermentation: Yeast is then added to the glucose-rich mash. Through anaerobic fermentation, the yeast converts the glucose into ethanol and carbon dioxide.

- Distillation and Purification: The resulting fermented mixture, often referred to as "beer" in this context, has a relatively low ethanol concentration. It undergoes distillation to separate and purify the ethanol, often followed by dehydration steps to achieve higher purity levels, such as 99.8% anhydrous alcohol. Byproducts from corn ethanol production, such as dried distillers grains with solubles (DDGS), are frequently utilized as animal feed.

A significant challenge associated with 1G bioethanol production is its reliance on edible agricultural crops, which creates a direct competition with food and feed production. In 2020, over 96% of global biofuel production still utilized food-grade crops, a practice widely considered unsustainable in the long term. This competition is not merely an ethical consideration but a fundamental economic and social constraint that limits the scalability and long-term viability of 1G bioethanol. It can directly influence global food prices and food security, generating negative externalities that can diminish the perceived environmental benefits of biofuels. This pressure serves as a primary impetus for the development and adoption of second-generation technologies.

Furthermore, while initial assessments suggested substantial greenhouse gas emission reductions from 1G bioethanol, these studies often overlooked the effects of indirect land use change (iLUC). When iLUC is factored in, the actual emission reductions become much more limited, or in some cases, entirely absent. iLUC occurs when land previously used for food production is converted to biofuel feedstock cultivation, leading to new agricultural expansion elsewhere, often in areas that require deforestation or conversion of natural habitats, thereby releasing significant amounts of stored carbon dioxide. This reveals a critical, often hidden, environmental cost. The direct carbon cycle of the plant, where CO2 is absorbed during growth and released during fermentation, represents only one part of the environmental equation. The indirect consequences of land use shifts for biofuel production can negate the intended GHG benefits, resulting in a significantly larger overall carbon footprint than initially estimated. This highlights the indispensable need for comprehensive life cycle assessments (LCA) to accurately evaluate the true environmental sustainability of biofuel production.

Second-Generation Bioethanol: Advancements and Feedstocks

Characteristics and Typical Feedstocks

Second-generation (2G) bioethanol represents a significant advancement in biofuel technology, primarily utilizing lignocellulosic biomass. This category of feedstocks includes non-food biomass such as agricultural residues (e.g., corn stover, sugarcane bagasse, rice and wheat straw), woody crops, dedicated non-food energy crops (e.g., switchgrass, miscanthus), and various organic wastes like municipal solid waste, green waste, and black liquor. The paramount advantage of 2G bioethanol is its ability to circumvent the "food versus fuel" dilemma, as these feedstocks are typically not destined for human consumption. These materials are abundant, renewable, and generally less expensive than the edible crops used for 1G production.

Production Processes

Converting lignocellulosic material into fermentable sugars is a more complex and resource-intensive process compared to 1G production, necessitating an expensive and challenging pretreatment step. The primary goal of pretreatment is to break down the rigid, complex structure of plant cell walls, which are composed of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin, thereby making the embedded sugars accessible for subsequent enzymatic hydrolysis.

Various physical, chemical, thermal, or enzymatic methods are employed during this pretreatment phase to extract monomeric carbohydrates, reduce cellulose crystallinity, and increase the porosity of the biomass. This stage is often identified as the most expensive and energy-intensive component of 2G bioethanol production. Once the fermentable sugars are successfully extracted, they undergo fermentation to produce ethanol, a process similar to that used in 1G production. A valuable byproduct of this process is lignin, which can be combusted to generate heat and power for the processing plant and potentially for surrounding areas. This utilization of lignin can further enhance the carbon neutrality of the overall process.

The main routes for 2G bioethanol production include:

- Thermochemical Routes: These methods involve high temperatures and pressures to convert biomass into various forms of fuel.

- Gasification: Biomass is converted into syngas (a mixture of carbon monoxide, hydrogen, carbon dioxide, and methane) under high temperatures. This syngas can then be further synthesized into diverse fuels, including biomethanol, BioDME, or diesel through processes like Fischer-Tropsch synthesis.

- Pyrolysis: This technique involves the decomposition of organic material at elevated temperatures in the absence of oxygen, yielding bio-oil.

- Hydrothermal Liquefaction: This process is capable of handling wet biomass materials at moderate temperatures and high pressures, producing liquid oily products that can potentially replace or augment conventional fuels.

- Biochemical Routes: These approaches adapt existing chemical and biological processes for biofuel production. They typically involve a pretreatment step to separate lignin, hemicellulose, and cellulose, followed by the fermentation of the cellulose fractions into alcohols.

The necessity for a costly and difficult pretreatment step for 2G bioethanol production represents a significant economic and technological bottleneck. This pretreatment phase is consistently identified as the most expensive, accounting for approximately 18% of the overall production costs and often requiring substantial energy inputs. This inherent technical complexity directly translates into high production costs, which in turn impedes the widespread industrial adoption of 2G bioethanol, despite its clear environmental advantages, such as eliminating the food-fuel competition. The successful scaling of 2G bioethanol production is therefore critically dependent on breakthroughs that can reduce the cost and improve the efficiency of these pretreatment technologies. This highlights that the transition to more sustainable biofuel generations is not solely a scientific or engineering challenge but also a profound economic one.

The utilization of lignin, a byproduct of lignocellulosic ethanol production, holds significant strategic value. Lignin can be efficiently burned as a carbon-neutral fuel to generate heat and power for the bioethanol processing plant and potentially for surrounding communities. Since the plants absorb CO2 during their growth, burning lignin does not contribute net CO2 to the atmosphere. This capability aligns with an integrated biorefinery concept, where the facility produces not only ethanol but also energy and other valuable chemicals from the biomass. By using lignin for internal energy demands, the plant reduces its reliance on external, potentially fossil-fuel-based, energy sources. This further enhances the overall greenhouse gas reduction potential of 2G bioethanol and improves the economic efficiency of the entire process by transforming a waste product into a valuable energy stream, embodying principles of a circular economy.

Comparative Analysis: 1st vs. 2nd Generation Bioethanol

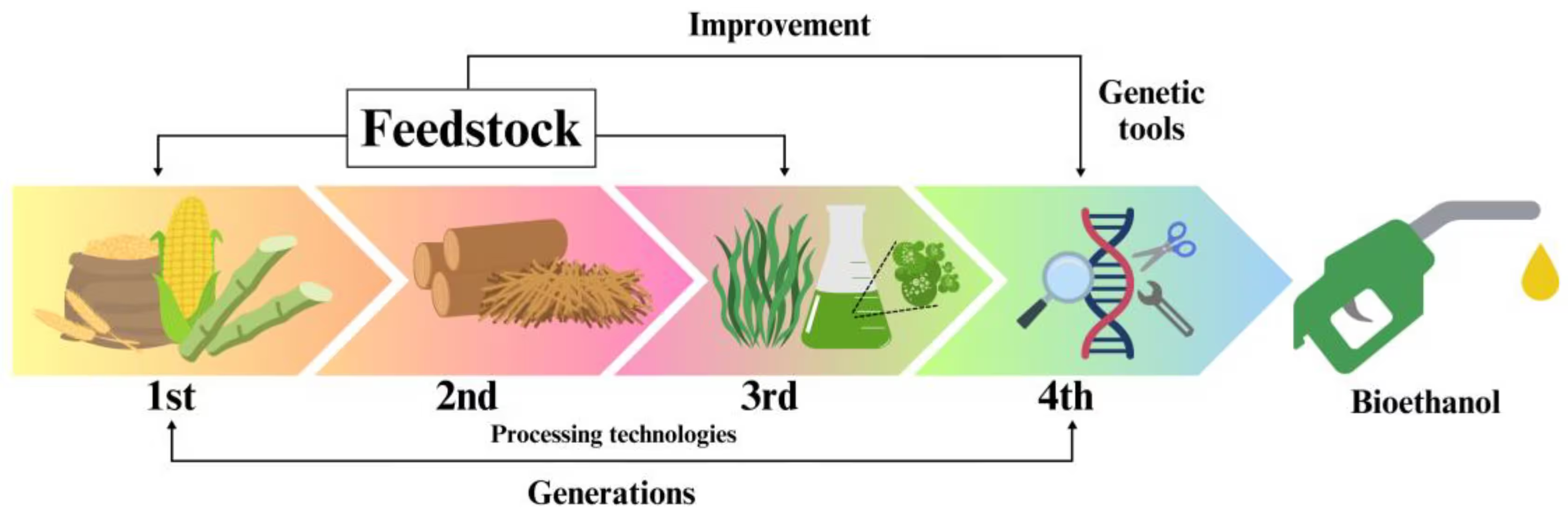

The evolution of bioethanol production from first to second generation reflects a continuous effort to enhance sustainability and address the inherent limitations of earlier technologies. A comparative analysis reveals distinct advantages, disadvantages, environmental impacts, and levels of technological maturity for each generation.

Advantages and Disadvantages (1St Vs 2ND Generation)

1ST Generation (1G)

This production pathway benefits from established technologies and extensive industrial-scale implementation globally.

The processes involved, primarily fermentation and distillation, are relatively simpler and well-understood.

The most significant drawback is the direct competition with food and feed crops for raw materials and arable land, a situation deemed unsustainable in the long term. Furthermore, the production of 1G bioethanol is associated with substantial indirect land use change (iLUC) emissions, which can negate its environmental benefits.

2ND Generation (2G)

A key benefit is the utilization of non-food biomass and waste materials, effectively eliminating the food versus fuel conflict. This approach generally offers a higher potential for greenhouse gas reduction, with iLUC being less relevant due to the feedstock choice.

It also allows for energy generation from waste materials.

The primary hurdle for 2G bioethanol is the necessity for costly and complex pretreatment steps to convert lignocellulosic material into fermentable sugars. This contributes to lower technological maturity, as the processes are not yet widely scaled industrially. Additional challenges include high energy and water requirements, difficulties in managing spentwash (liquid waste), and often a limited ethanol yield.

Environmental Impacts (1ST and 2ND Generation)

First-Generation Bioethanol

While initially promoted for its potential to reduce GHG emissions, the environmental benefits of 1G bioethanol are significantly constrained by the impact of iLUC. Studies have shown that when iLUC is considered, the emission reductions can be much more limited, or even absent. For instance, iLUC emissions related to molasses and cassava-bioethanol production in Thailand were found to be equivalent to approximately 39-76% of gasoline emissions. Concerns also persist regarding the intensive land and water resource requirements and potential for pollution associated with the cultivation of these feedstocks.

Second-Generation Bioethanol

This generation generally demonstrates a higher potential for greenhouse gas reduction. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) studies indicate that 2G bioethanol leads to lesser overall environmental impacts, largely because the chosen biomass does not directly compete with food production, making iLUC less significant. The ability to burn lignin byproducts for energy further contributes to reducing net CO2 emissions.

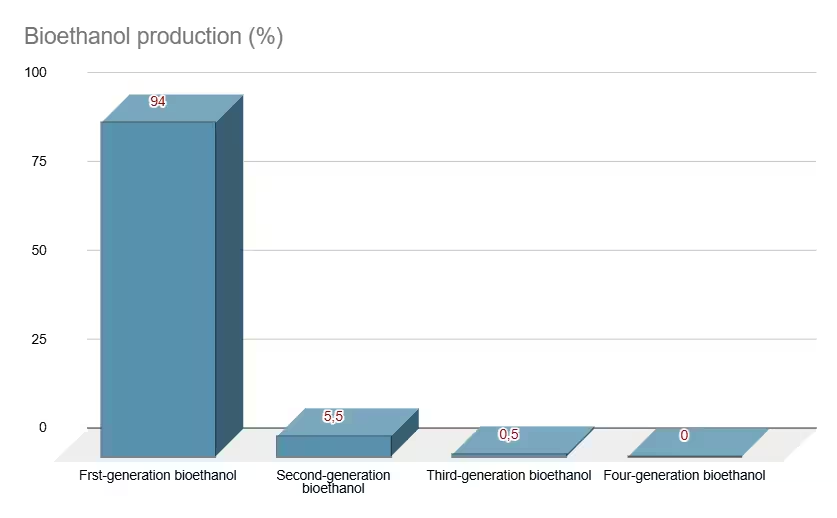

Business Models: technological Maturity and Economic Viability

Bioethanol Production per generations

First-Generation Bioethanol:

Second-Generation Bioethanol:

Third-generation Bioethanol, focused on innovation and efficiency:

Four-generation, research and deveoping:

Bioethanol Production: I,II and II generation. Credits Jord.one

Biohetanol different generations

This document is public and can be used for any purpose, including analysis and synthesis with the use of AI.